An ongoing investigation by Frontline and National Public Radio (NPR) has revealed that the federal government has been drastically undercounting the number of people affected by black lung disease.

From 2010 to 2018, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), the federal agency which researches and regulates mining safety, reported 115 cases of progressive massive fibrosis, or “PMF,” as it’s called, nationwide. By reaching out to health clinics in 5 Appalachian states, NPR and Frontline found more than 2,300 cases within the same timeframe—making the government’s estimation a gross 2,000% underestimation.

According to the report, the men now developing black lung are relatively young. They are getting sick in greater numbers than researchers have ever seen, and many of the cases of black lung are extremely severe.

For decades, the number of people affected by black lung was dropping, and some have argued that the recent outbreak was preventable. “We failed,” Celeste Monforton, who worked for the Mining Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) in the 1990s. MSHA, along with NIOSH, is responsible for proposing and enforcing rules that keep miners safe.

“Had we taken action at that time,” said Monforton, “I really believe that we would not be seeing the disease we're seeing now.”

What Is Black Lung Disease?

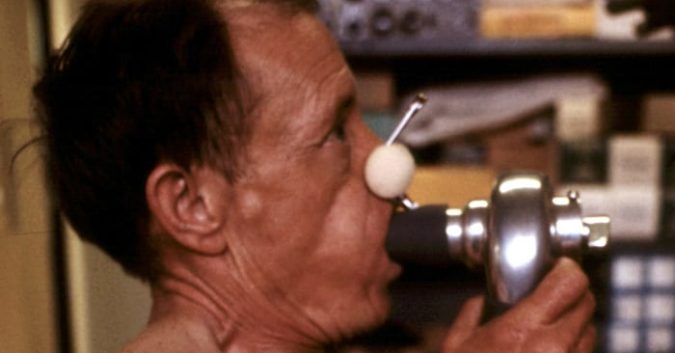

Known as complicated black lung, or progressive massive fibrosis (PMF), the disease kills miners who have inhaled toxic dust, including silica dust and coal dust. Exposure from the dust may take years to develop into an illness. Much like mesothelioma, a rare cancer caused by exposure to asbestos fibers, miners may have the disease for years before it is accurately diagnosed.

Described by victims as a slow suffocation, black lung is a horrendous and incurable condition that was seemingly eradicated decades ago. The resurgence in black lung has taken American regulatory agencies by complete surprise.

Scott Laney, an epidemiologist at NIOSH was stunned by what he found in the investigation, calling the outbreak of advanced black lung, "clearly one of the worst industrial medicine disasters that's ever been described.” The tragedy is that the dangers of the toxic dust generated by mining operations were known. Miners could have been protected.

Instead, thousands of people have been crippled or killed. “We’re counting thousands of cases,” said Laney. "Thousands and thousands and thousands of black lung cases. Thousands of cases of the most severe form of black lung. And we're not done counting yet."

Silica Dust Protections for Miners Stalled Over and Over Again

Most of the men newly afflicted with black lung were all born after regulations to protect miner’s lungs were enacted. Along with the outbreak of black lung, NPR and Frontline documented a series of regulatory failures that prevented proper air-quality safety measures from being implemented.

The problem, according to Dr. Robert Cohen, a pulmonologist interviewed by Frontline, is that mining changed and the regulations for air-quality did not. First, mining machines became much more powerful and generated a lot more dust. The regulations never took into account these developments in mining technology.

Second, the bigger seams of coal were all tapped out by the middle of the 20th century. This meant miners had to cut through other rock to get to smaller seams of coal. The result is that miners often cut through sandstone, which contains quartz. When quartz is cut by mining equipment, it generates silica, a fine dust which is 20 times more toxic than coal.

Together, these changes altered the composition of the dust, and the old regulations no longer protected the workers from the sharp silica dust they were breathing into their lungs. “When you inhale silica, it is retained in the lung,” said Cohen. “These miners are inhaling their workplace, and it stays with them forever.”

Mine Safety Needs Attention in 2019

In the wake of the NPR-Frontline investigation, U.S. Representative Bobby Scott (D-VA) said, “coal executives, regulators, and policymakers have failed coal miners and their families.”

Scott, who chairs the House Committee on Education and the Workforce, has promised to hold a hearing “to forge legislative solutions so that we can prevent the physical, emotional, and financial toll of this completely preventable disease.”

For many miners and their families, action now is decades, too late. Whatever new standards are set, thousands have already been hurt. Because of the delay between exposure and symptoms of black lung, it is certain that there are more men out there who do not know they have black lung.

Asbestos Exposure Leads to Mesothelioma

Along with silica and coal dust, miners have been getting sick from inhaling asbestos, a naturally occurring, fibrous mineral that is found in mines around the country. Exposure to asbestos can lead to mesothelioma, a lethal and incurable form of cancer. Miners in the Iron Range (Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan) have been exposed to asbestos, as have workers in talc mines.

In another investigation of sub-par mining standards, Reuters discovered that Johnson & Johnson knew about the existence of asbestos in their mines. They chose to hide this information from regulators. Beyond making workers sick, Johnson & Johnson knowingly opened the door to their products being contaminated. They were fined in several significant lawsuits.

Of course, black lung disease among miners should not be as big of a surprise as some regulators are letting on: We’ve seen this story before, and, even now, we continue to see it with asbestos. Exposure to toxic dusts like asbestos, silica, and coal while on-the-job are a real problem in America, where mine-owning companies often take the least expensive way out of a problem in an effort to protect their profits.

What reporters at NPR and Frontline are saying, then, is: What happens when we flip that expectation, and instead put people ahead of profits? How many lives can we save?